Embracing Disruption

Investing in China’s State Owned Enterprises: A Deep Dive

For many years, investing in China’s State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) has typically been viewed by international investors as, at best, a low-quality proxy for China’s economic growth. They have been synonymous with low profitability, questionable governance, and poor shareholder returns.

Summary

- Despite some scepticism towards SOEs, a great deal of progress has been made.

- Debt burdens have eased, stock incentive schemes for management and employees are more widespread, cash flows are improving, and there is a growing focus on share-holder returns through higher dividends and buybacks.

- Tarring all SOEs with the same brush and assuming they add little economic value is, in our view, misguided. Selectivity remains essential.

The reality, however, is that, given the make-up of China’s economy and the composition of equity indices, an allocation to China equities will inevitably include meaningful investments in SOEs. And this is not necessarily a negative. Indeed, in the recent challenging equity market environment, SOEs as a whole have actually outperformed private enterprises quite convincingly.

In our view, there is a significant gap between the perception and reality of SOEs. In some areas – for example, China’s goal of carbon neutrality – SOEs are at the forefront of crucial change. In this article we seek to address key issues around investing in SOEs and why we believe they can offer a valuable opportunity set to investors.

SOEs as proportion of China’s equity market – reduced size, but still a big influence

Since economic reform and opening-up policies began in 1978, China’s SOEs have undergone a long process of gradual and progressive transformation. Today, SOEs are a slimmed down version of their former selves. For example, the number of central SOEs – that is, SOEs controlled by the central government – has shrunk by close to 20% (from 117 to 97) in the years from 2012-2023. There has also been significant M&A activity across the SOE landscape, with businesses looking to improve efficiency and resource allocation.

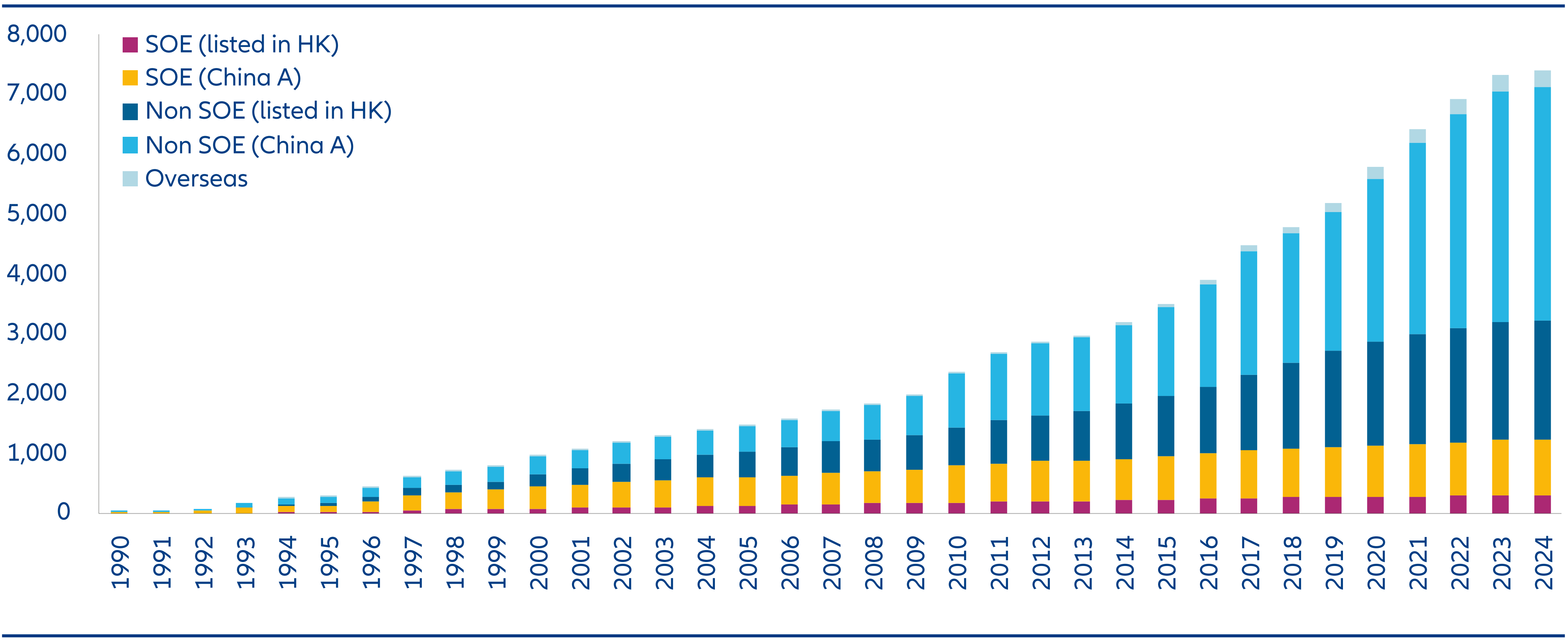

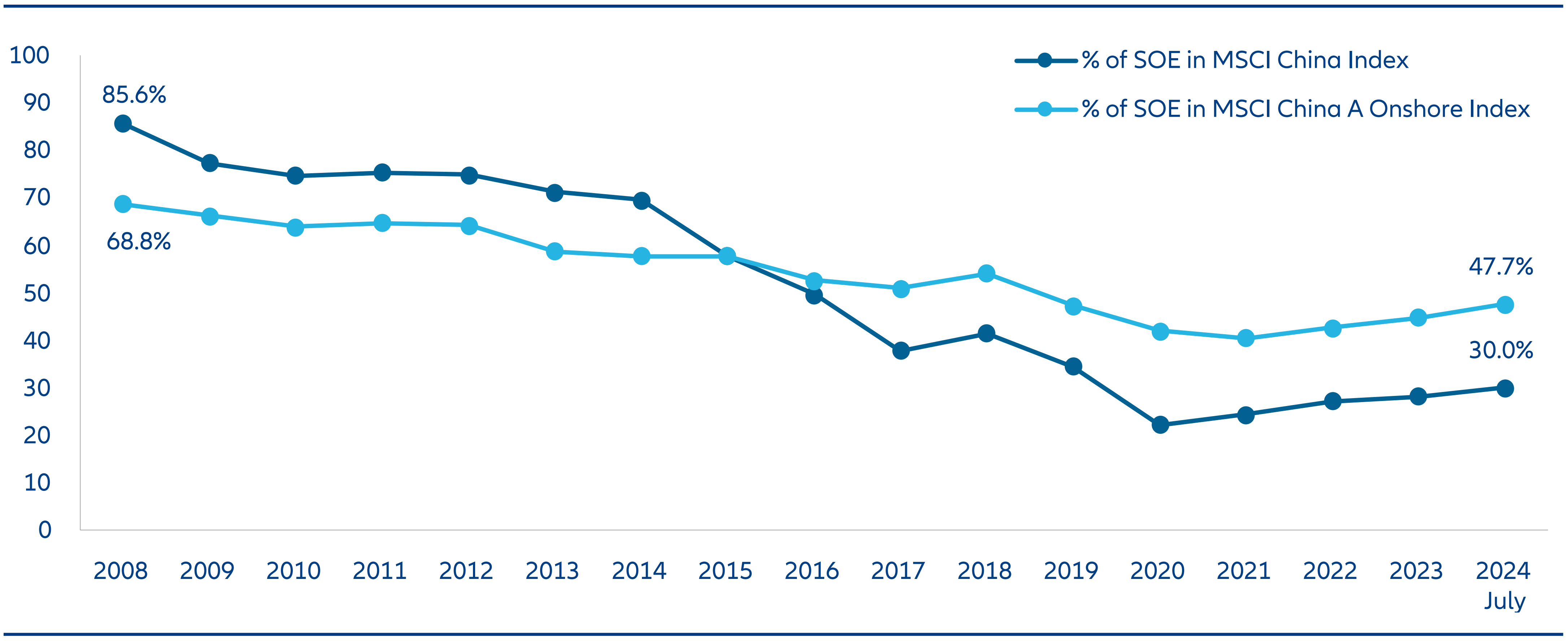

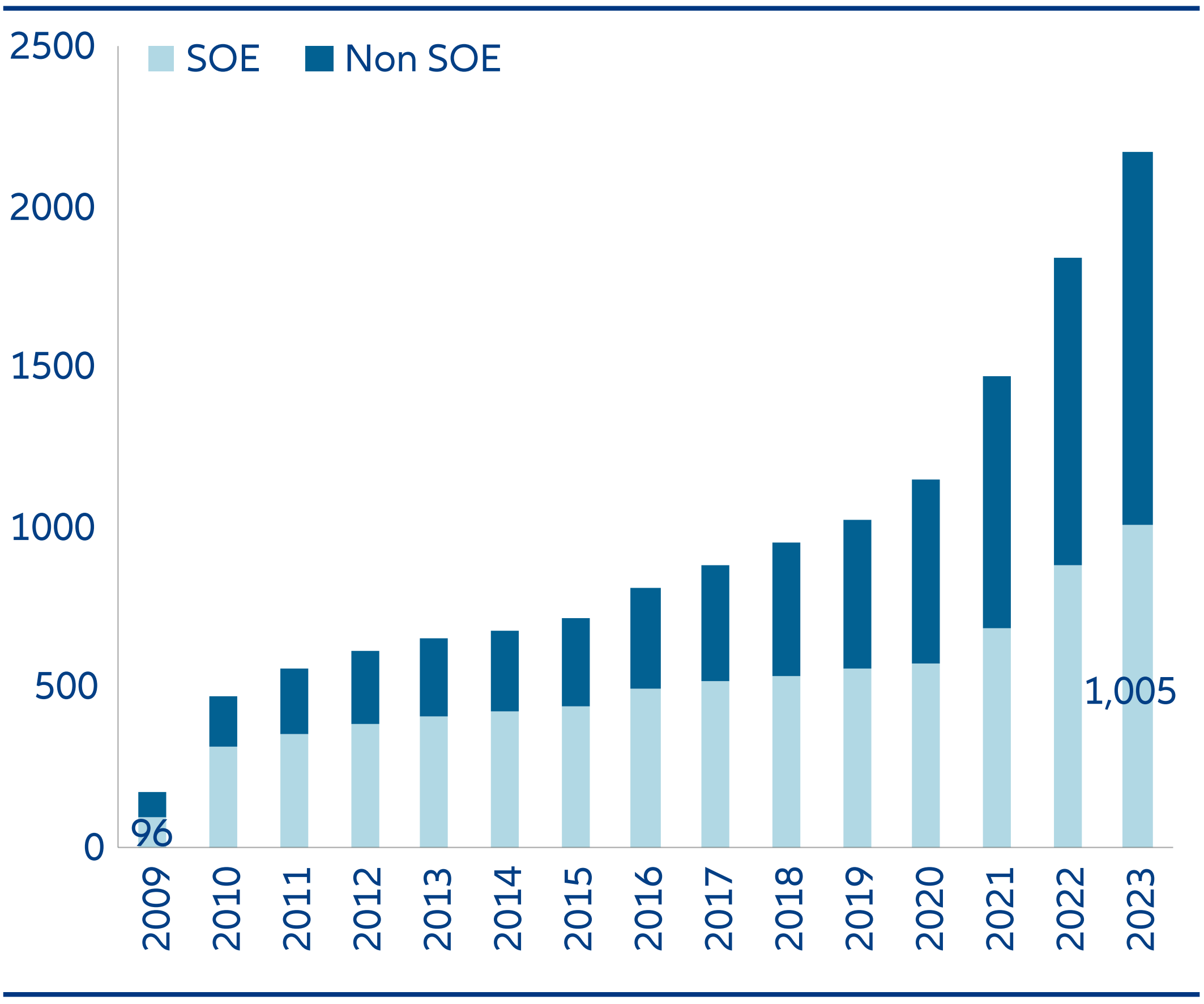

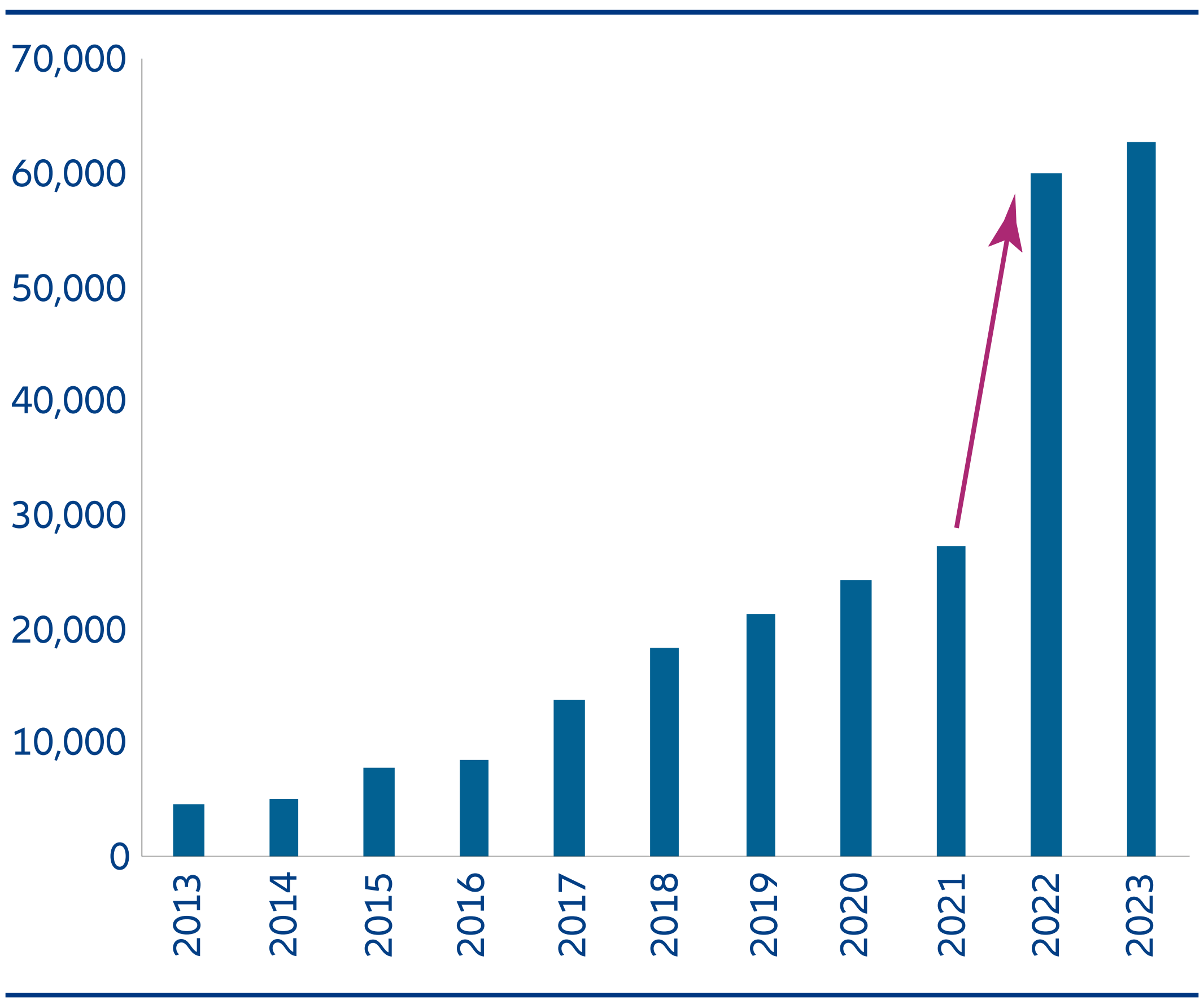

So while the overall number of listed SOEs has increased over the years, they have come to represent a smaller part of the overall universe, particularly as private sector investment opportunities have mushroomed (Chart 1). This change is also reflected in terms of market capitalization. Twenty years ago, when international investors were mainly restricted to offshore markets, SOEs accounted for over 90% of the MSCI China Index. In comparison, SOEs currently account for under 50% of the China A market (Chart 2).

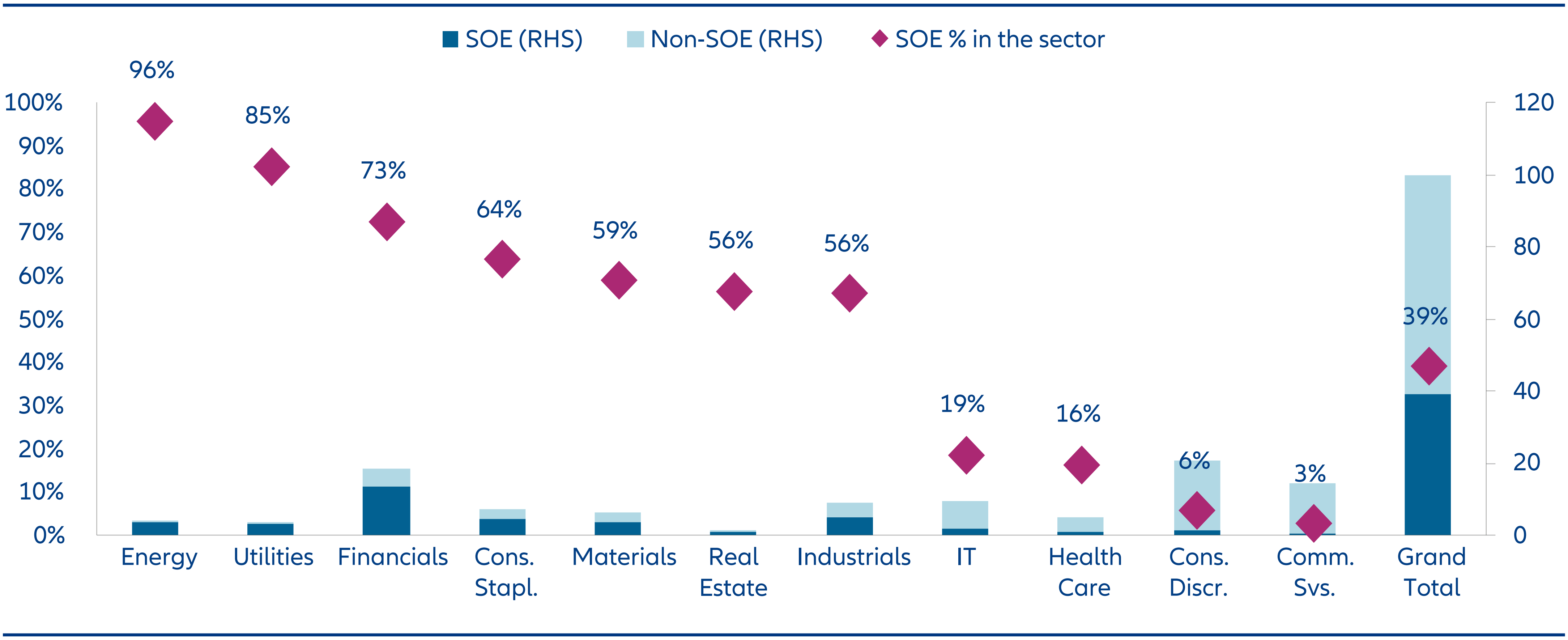

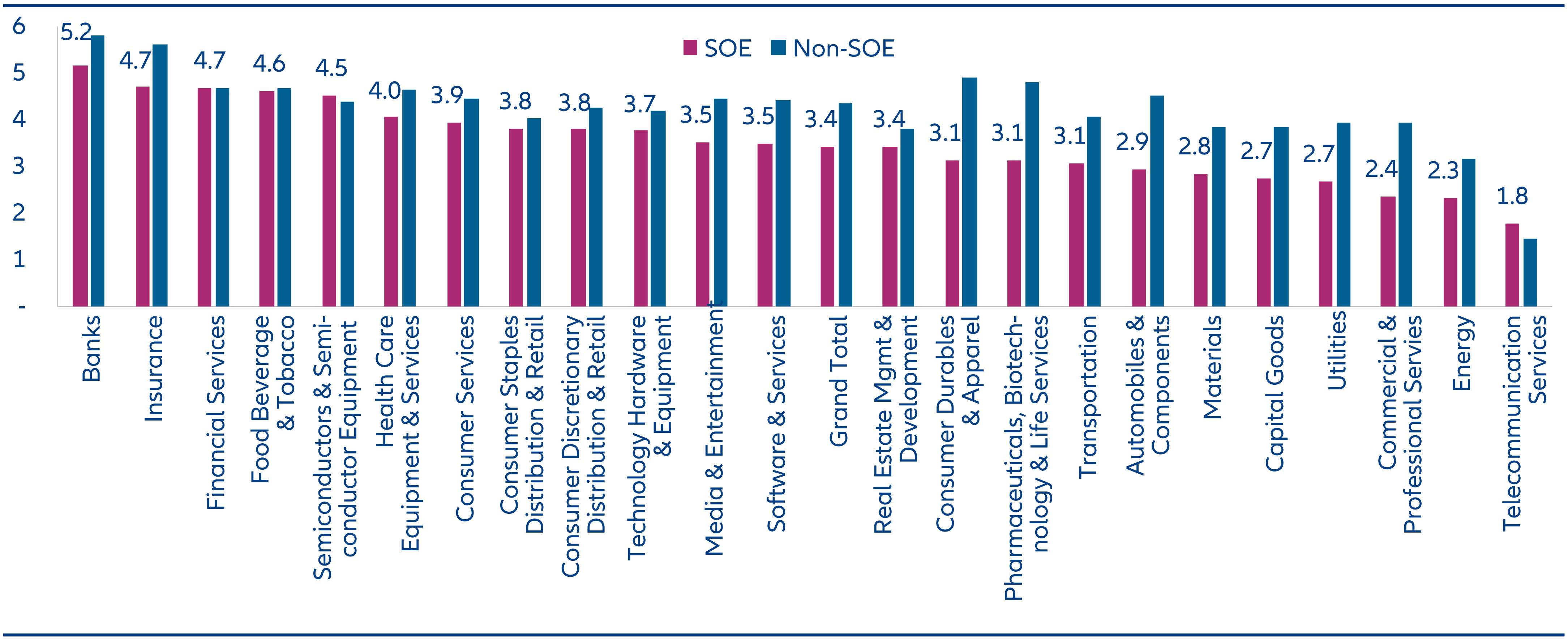

Although their relative influence has decreased, SOEs are still an important part of China’s equity markets, as well as the country’s overall economic structure. Indeed, SOEs continue to dominate in sectors seen as strategically important, including energy, power utilities and financials (Chart 3). And since 2021, mainly as a result of relative share price outperformance, the SOE weight in China equity markets has increased.

Chart 1: Number of Listed Companies in onshore and offshore China equity markets since 1990

Source: (left) Wind, Allianz Global Investors, as of 30 June 2024

Chart 2: SOE weight in onshore and offshore markets over time

Source: Wind, Bloomberg, Allianz Global Investors, as of 31 July 2024

Chart 3: MSCI China All Shares Index: SOE vs Non-SOE weight by sector

Source: Wind, Allianz Global Investors, as of 31 July 2024

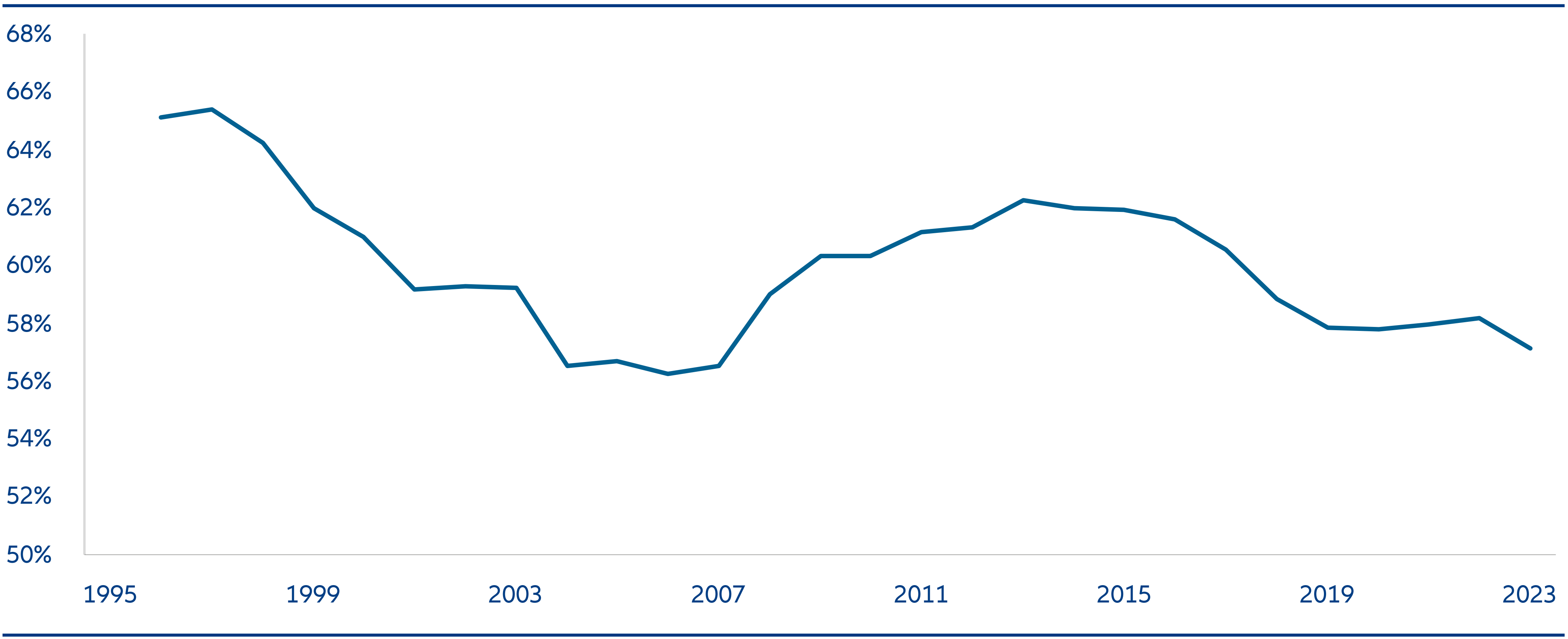

Chart 4: SOE debt to asset ratio over time

Source: Wind, National Bureau of Statistics of China, HSBC Equity Research, Allianz Global Investors, as of 31 July 2024

“SOE Reform”

It has long been recognized within China that SOEs require a significant overhaul if they are to be transformed into more competitive and modern enterprises. Indeed, SOE reform has taken place over several decades.. It has consistently been a core element in China’s economic planning process – with the goal of improving financial performance – but the thinking about how reforms should be implemented has evolved.

For example, in the last decade there has been a push for SOEs in strategically important industries (such as energy supply, transportation buildout, and semiconductors) to consolidate. While the results have been mixed, some of these cases have certainly resulted in improvements to capital allocation as consolidated Chinese SOEs put more focus on gaining market share on a global stage instead of competing against each other.

There has also been a significant improvement in the balance sheets of many SOEs, with a notable reduction in debt levels over the last decade in particular. This was partly helped by supply side reform, where the government applied a ceiling to the overall production capacity of certain upstream industries like materials. In addition, the recovery in some commodity prices has also helped boost margins.

From an investability perspective, some of the more relevant reforms have come about as a result of SOEs becoming more market-oriented in their resource allocations. This has typically been in areas such as consumer products and services, health care, and construction machinery. Successful SOEs in these areas often share some common traits with private enterprises: a workforce incentivized through employee stock ownership plans, professional managers with a strong industry background, the introduction of independent board members, well-established distribution networks, and recognized brand names developed over years.

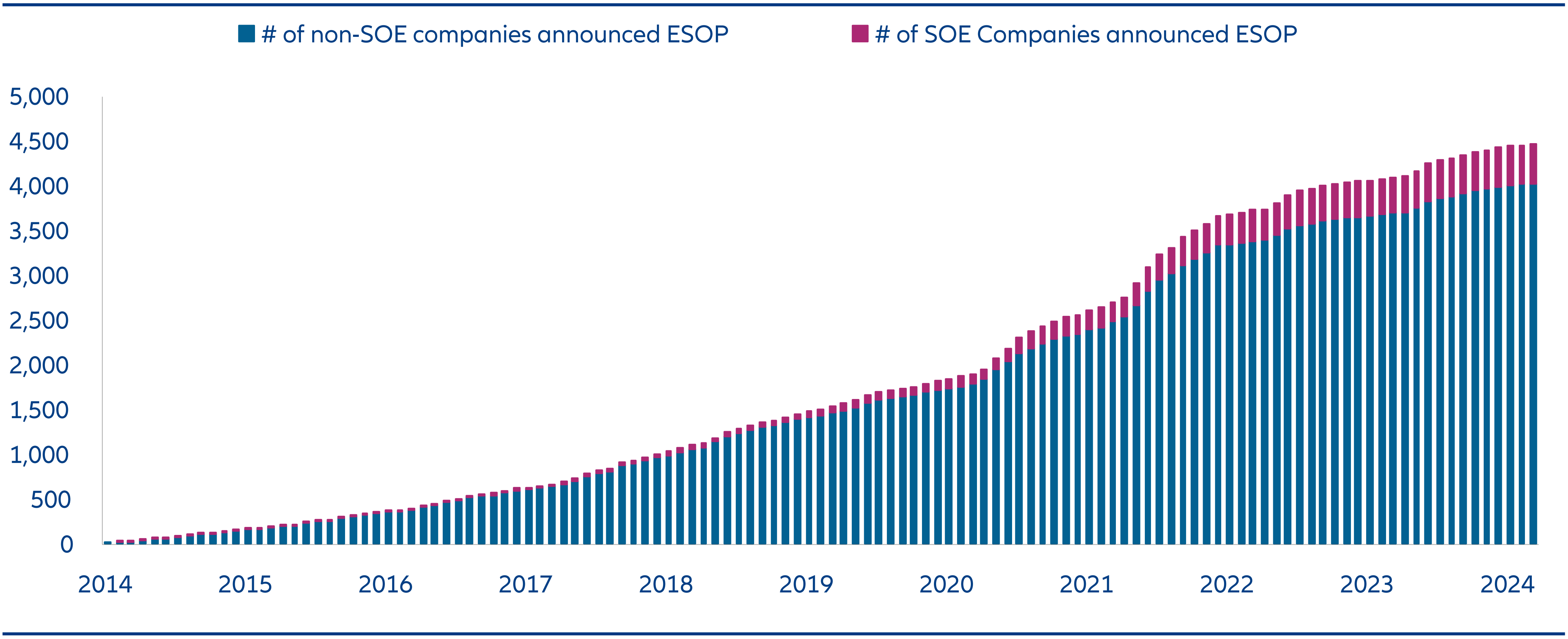

It has also been encouraging to see a rising number of SOEs adopting employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs), which help to better align management interest with that of minority shareholders. Properly designed and structured, these can be an important indicator of a positive corporate governance and business culture.

Chart 5: Number of China A-share companies with Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOP)

Source: Wind, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, as of 31 March 2024.

Recent government initiatives have included the use of financial targets for SOEs, such as return on equity and net profit growth. And in the last year, the government has taken an important additional step, selectively assessing SOE management based on market capitalization. Tying financial market indicators with performance evaluation for senior management in SOEs may, over the longer term, have a more significant impact for investors.

Dividend yields and share buybacks – a new trend

A notable recent development in China equity markets has been a marked increase in dividend payouts and share buybacks; and SOEs have been at the forefront of this.

This change was spurred by a regulatory push earlier in 2024. Enhancing shareholder returns has become a key focus of the State Council – effectively the national cabinet – as well as the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), in a move that echoes recent governance changes in Japan and Korea.

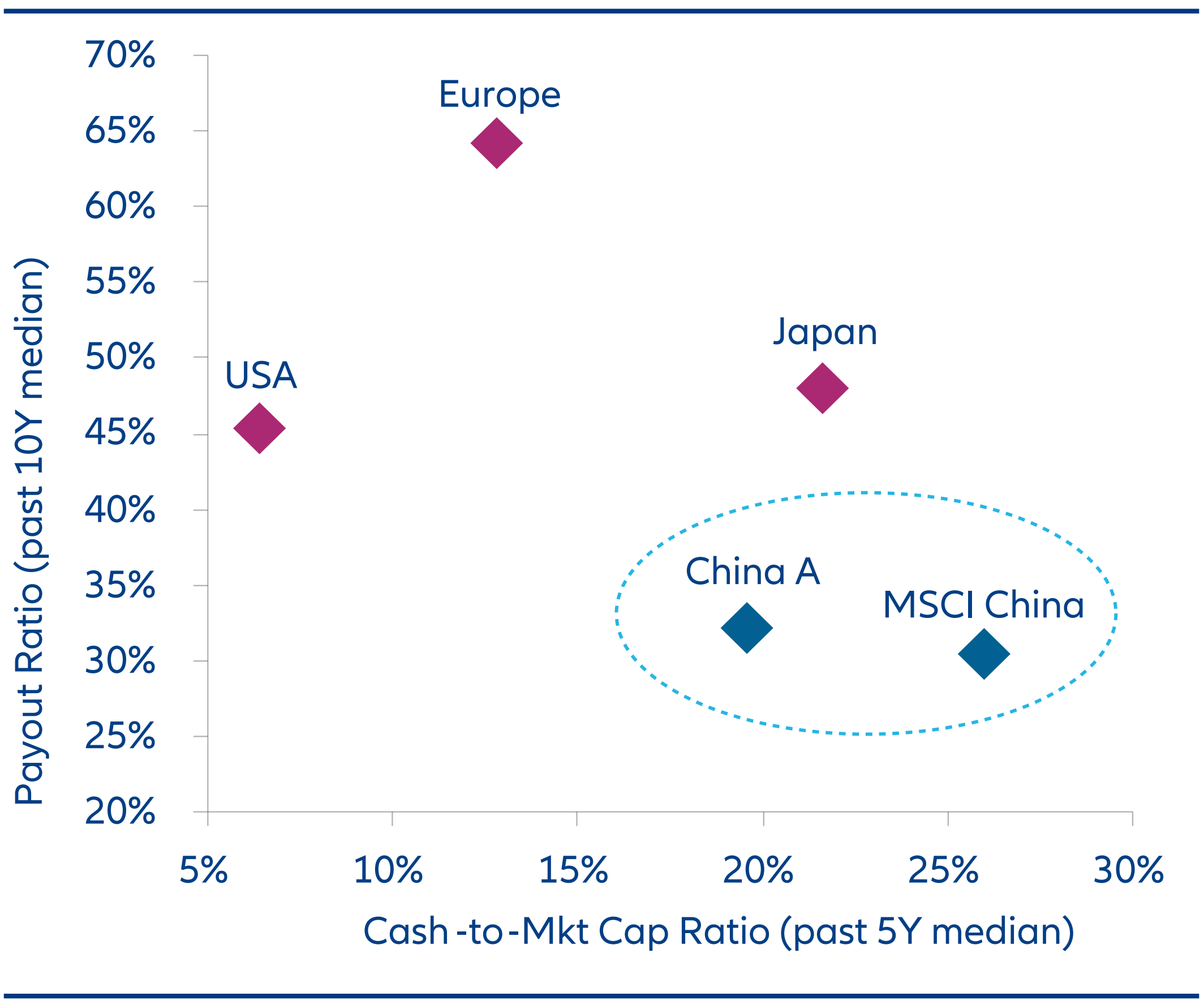

From a fundamental perspective there certainly appears to be room to increase dividends and share buybacks. Chinese companies in aggregate (ex-financials) have around USD 2.3 trillion of cash on their balance sheets, equivalent to around 27% of their prevailing market cap – a considerably higher level than in most other global markets. And cash flows are expected to improve, especially for larger companies in more mature sectors, as the structural economic slowdown feeds into reduced capex requirements.

Chart 6: Cash-to-Market Cap and Dividend Payout Ratios of China equities

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, as of 25 April 2024.

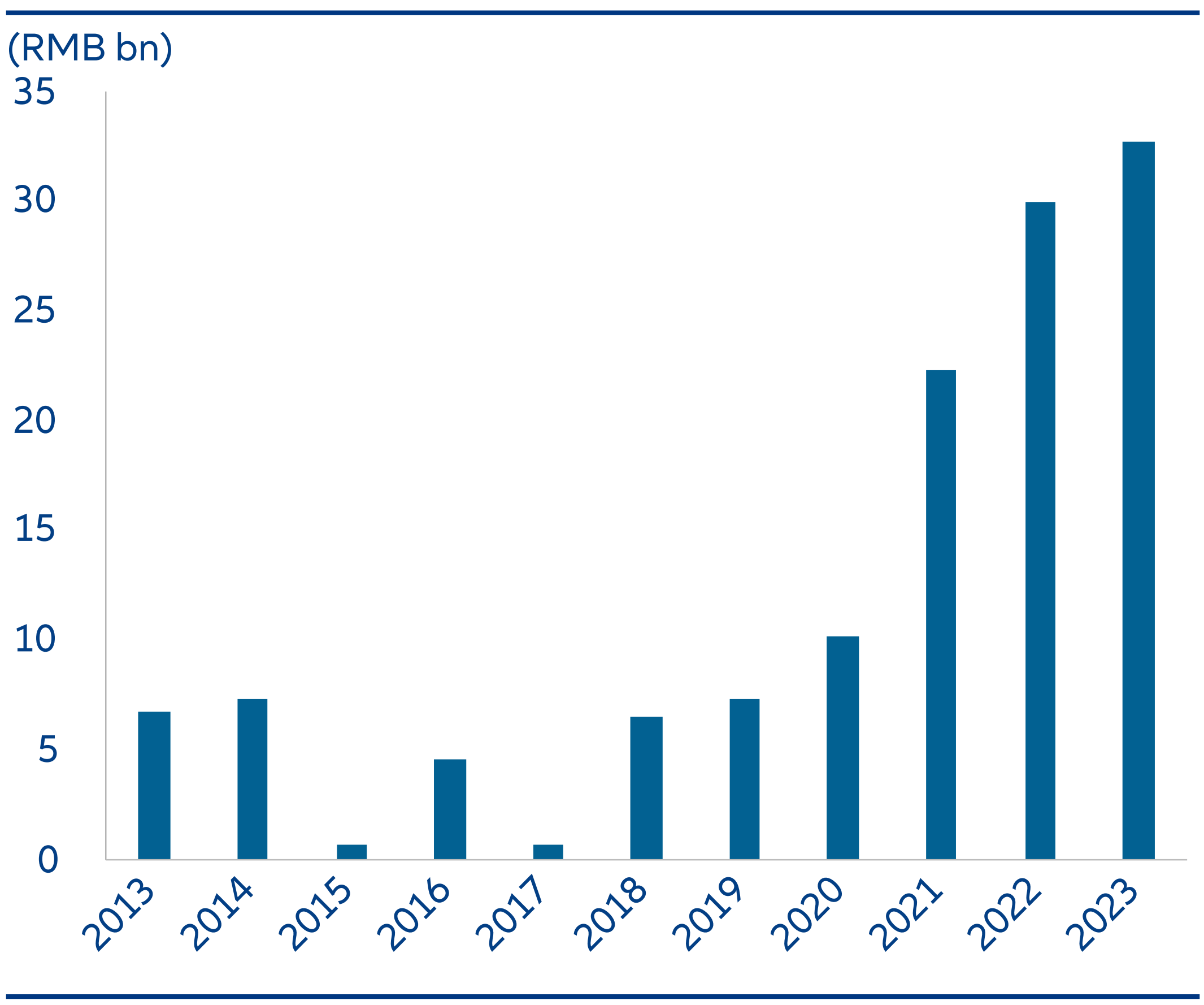

Chart 7: China A-Share SOEs share buybacks

Source: Wind, UBS China Equity Strategy, as of 31 December 2023.

In terms of dividends, China corporate payout ratios of around 30% are relatively low in both Asian and global contexts. And while the momentum for share buybacks has strengthened in Hong Kong-listed stocks in recent years, it is still at a relatively nascent stage in onshore markets. China A-Share companies bought back shares equivalent to only around 0.2% of free float market cap in 2023. As a point of reference, S&P 500 share buybacks have, on average, been 2.1% of listed market cap each year in the last decade.

With SOEs now more incentivized – and pressurized – to enhance shareholder returns, they have been at the forefront of these market developments. The dividend payouts of SOEs increased to CNY 1,237 billion in 2023, around 67% higher than 2019 as a pre-Covid comparison.

Total share buyback volumes by listed SOEs rose to CNY 33bn in 2023, close to a six-fold increase since 2019 (Chart 7).

A further development is the higher frequency of dividend payments. Bellwether stocks such as stateowned banks have historically only paid dividends once a year. In their latest quarterly reports the banks mapped out plans to also pay interim dividends in future. This should be an appealing feature, especially for domestic retail investors.

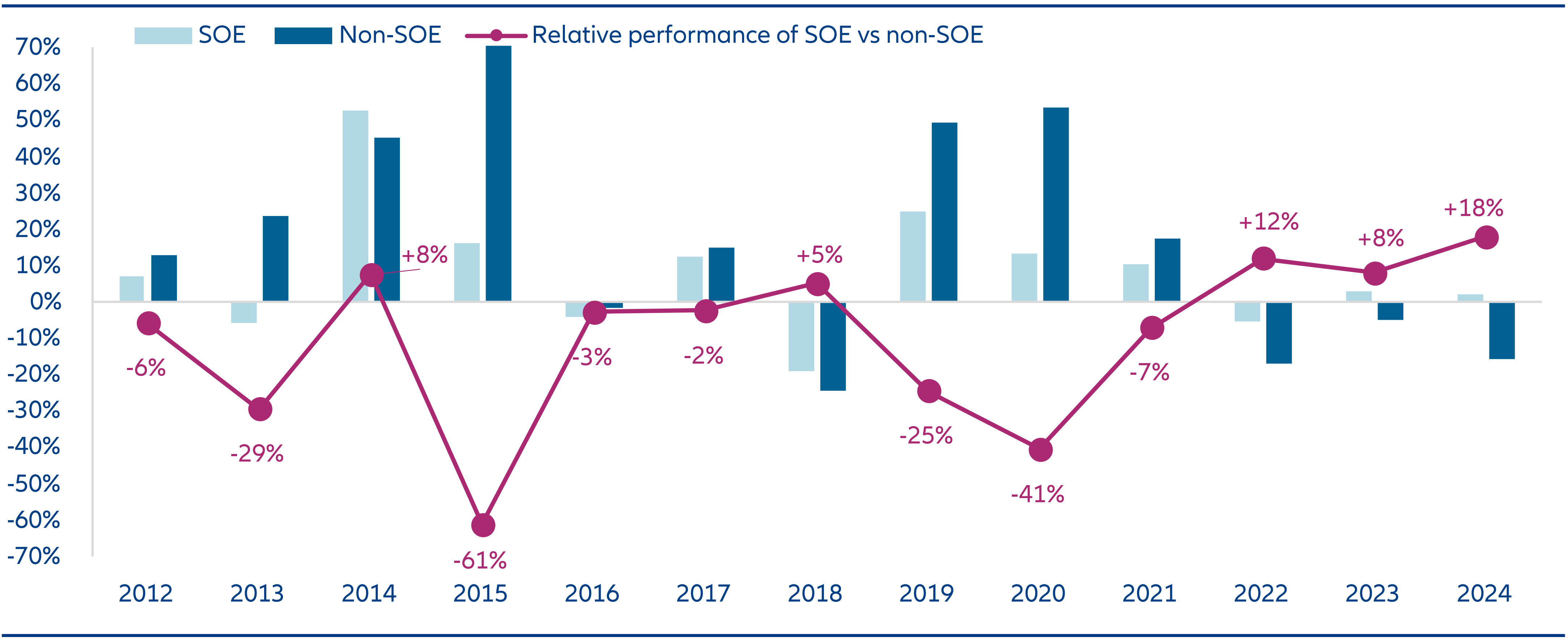

After a sustained period of listed SOEs underperforming non-SOEs, the last three years have seen a significant reversal (Chart 8). There are several explanations.

Chart 8: Calendar year returns of SOEs and non-SOEs

Source: Wind, Allianz Global Investors, as of 6 August 2024. The above calendar year return is derived based on changes in aggregate market cap of SOE vs non SOE companies in China A-shares universe.

A key factor has been the relatively strong performance of sectors which are dominated by SOEs. Over the last three years, energy, utilities, telecom, and financial stocks have led the way. This year, Chinese banks reached all-time share price highs. In contrast, other sectors which have been more vulnerable to reduced earnings in the weak macro environment have struggled.

As a reflection of the economic situation, domestic Chinese investors have also come to see SOEs as a defensive safe haven, given their more robust balance sheets, access to funding, and more resilient business models. With government bond yields declining significantly, higher dividend yield stocks – many of which are SOEs – has also been a key investment theme. And, conversely, there has been the impact of government policy on private enterprises in the internet, education, and property sectors, which has resulted in a significant share price reset amid the uncertainty.

A new focus on ESG & Sustainability

In our view, there has been a very evident shift in how many Chinese companies view their ESG and sustainability responsibilities. SOEs have been in the vanguard. Qualitatively we see this in the way companies have become more open to dialogue and, along with this, improving levels of information disclosure. Quantitatively, this can be measured by the increased number of companies providing ESG reports (Chart 9). An important catalyst has been regulatory pressure. For example, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC) has announced a mandatory requirement of ESG full disclosure for central SOEs. This is happening alongside a step-up of ESG disclosure guidance by the mainland China stock exchanges.

The addition of financial market performance as part of the KPI’s of SOE management teams has also helped to improve the alignment of their interests with minority shareholders.

A good example is Kweichow Moutai, the largest constituent of the MSCI China A Onshore index. Moutai is a leading white liquor brand in China with a dominant and well-entrenched market share. It is also an SOE. Over time we have observed a distinct change in the corporate culture. Previously, Moutai provided extremely limited disclosures on their business activities and access to senior management was highly restricted, at best. They now proactively reach out to investors to discuss company proposals before voting, and publish an increasingly comprehensive ESG report that is even available in English.

Chart 9: Number of China A companies with ESG/CSR disclosure

Source: Wind, Allianz Global Investors, as of 31 December 2023.

Chart 10: Kweichow Moutai cash dividend history

Source: Wind, Allianz Global Investors, as of 31 December 2023.

Perhaps the biggest change, however, is their use of cash. Moutai was heavily scrutinized in previous years for its socalled “government donations”, a reference to payments made to its key local government shareholder but not to minorities. The dividend policy was radically revised in 2022; in parallel, the company committed to a dividend payout ratio of at least 75%.

So while SOEs may have a reputation for poor corporate governance, the reality is that third-party ESG scores for many SOEs have improved significantly, and in some sectors are close to or higher than non-SOE companies.

Chart 11: MSCI Governance Score by industry group in China

Source: MSCI, Allianz Global Investors, as of 3 September 2024.

Conclusion

Despite the skepticism towards SOEs, a lot of progress has been made over the years. Debt burdens have eased, stock incentive schemes for management and employees are more widespread, cash flows are improving and there is a growing focus on shareholder returns through higher dividends and share buybacks.

Of course, there is still a long way to go, and many SOEs continue to face challenges including low levels of efficiency and questionable governance. Nonetheless, tarring all SOEs with the same brush and assuming they add little economic value is, in our view, misguided.

While the SOE exposure in our portfolios has typically been lower than the benchmark (e.g. for our China A-Shares strategy: 40.6% versus 47.4%, as of 31. July 2024), SOEs have been some of the strongest contributors to relative performance in recent years. The key, in our view, is to understand the people behind the business, their aspirations and incentives, as well as their execution capability. This requires on-the-ground work to engage with management, cross checking along the supply chain, and using our Grassroots® Research network.