Why Asian high-yield credit may soon turn from laggard to leader

Summary

Asian high-yield bonds delivered positive returns in 2020 but underperformed other assets. At first glance this may seem counterintuitive. Asia can offer more income and relative value than the rest of the world at a time of record low interest rates and concerns over high valuations. An allocation to Asian high yield is very much a high-conviction call on China, which has led the recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic. A closer look at country, sector and investor dynamics suggests that the long-term track record and outlook for Asian high yield remains compelling.

Higher income and relative value

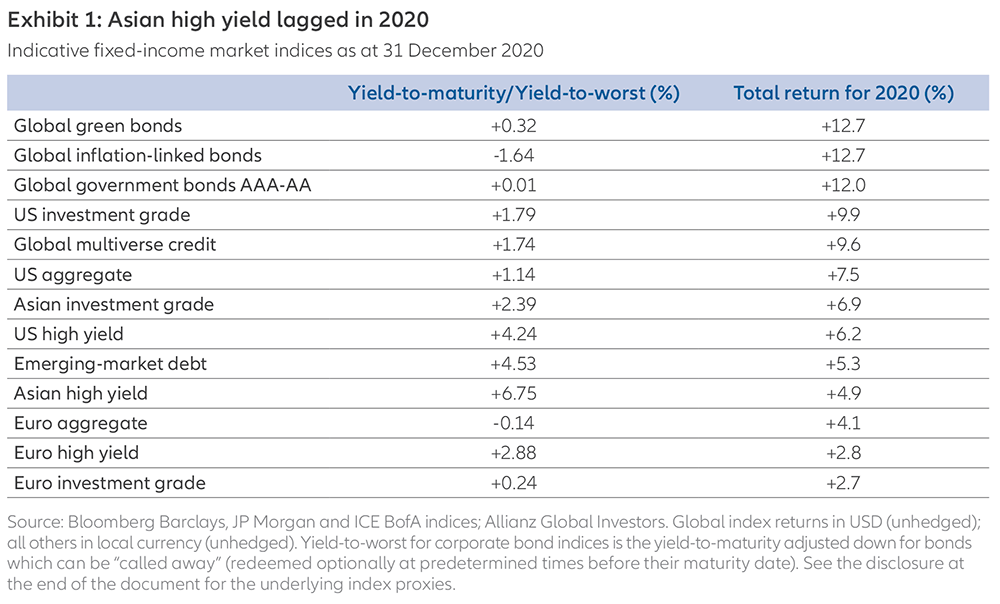

Most fixed-income sectors finished 2020 ahead of the Asian high-yield bond market. The full-year total return of the asset class, often represented by the JP Morgan Asia Credit Index (JACI) Non-Investment Grade, lagged as investors demanded a higher yield to compensate for credit risk (see Exhibit 1). The JACI high-yield index tracks US dollar (USD) denominated bonds of corporates, sovereign and quasi-sovereign issuers in Asia ex-Japan.

Yet investing in Asian USD (offshore) bonds benefits typically not only from greater liquidity, centred around new issues and larger benchmark bonds, but also from exposure to issuers with generally stronger balance sheets and greater funding flexibility. In contrast, the region’s onshore markets are more mixed. China’s onshore corporate debt market is about 10 times larger than the offshore USD and Chinese yuan (CNY) markets together. An estimated 75% of Chinese corporate issuers are not yet rated by global credit agencies.

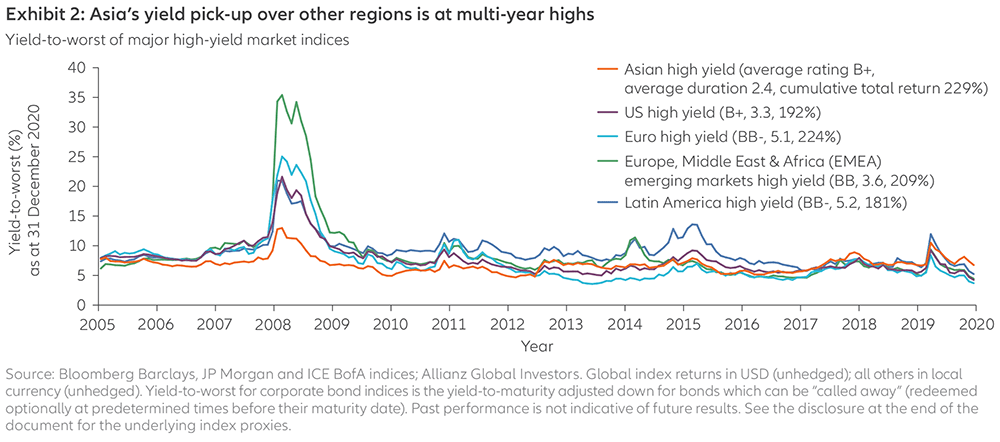

Moreover, the yield pick-up Asia offers over other regions is at multi-year highs since the JACI index was introduced in 2005 (see Exhibit 2). Yet the Asian high-yield market has the same average credit rating as its lower-yielding US counterpart. Additionally, Asian high-yield bonds have lower average duration (interest rate) risk than other regional markets – at a time when corporate debt seems much more vulnerable (compared with previous years) to losses from any sudden volatility in interest rate expectations.

From the viewpoint of higher yields and lower duration, Asia’s outperformance potential looks strong, both in hindsight and going forward (see Exhibit 2). Since 2005, the cumulative performance and resilience of Asian high-yield bonds in aggregate (up 229%) has been better than other regions. This comes despite the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, and notwithstanding the heightened volatility in 2018 from China’s trade conflict with the US and a push for onshore deleveraging, which weakened regional demand.

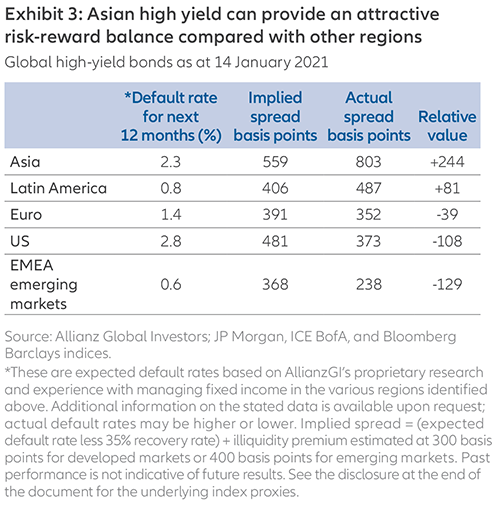

There are several other metrics which suggest Asian high-yield credit may soon turn from laggard to leader. The offshore market’s default rate for 2020 is estimated at 3%, which is much lower than other major developed and emerging markets. We expect the default rate for the next 12 months, weighted by the par (redemption) value of outstanding bonds, to be lower for Asia (2.3%) than the US (2.8%).

Another useful risk measure to consider is the market’s “implied spread”. This can be derived from forecasted default and loss recovery rates, and also from taking into account the comparably wider bid-ask (liquidity) spreads found in high-yield and emerging markets. The difference between the “implied spread” and the “credit spread” (yield premium over higher-rated government bonds of similar maturity) can be a good gauge of the risk-reward balance in the global high-yield market. By our estimates, Asia now ranks as the most attractive on this “relative value” basis (see Exhibit 3).

After such a strong rally in core rates and credit markets, driven very much by central bank bond purchases, we see investors becoming increasingly worried about risk asset valuations. Safe-haven assets and duration gains may no longer help hedge portfolios with as much upside. Risk premiums on Asian USD bonds have not compressed as much as in the US or Europe because most Asian central banks have not been buying corporate debt as part of their market liquidity operations.

In 2021 we expect attention to shift to higher-yielding assets that offer relative value and greater protection from any unexpected macroeconomic shocks. This change in focus should bode well for Asian high-yield credit. To understand why, it’s important to delve into China’s growth and debt dynamics, the country’s property sector and state-owned companies, as well as credit market prospects in East and South Asia.

Strong China and regional growth

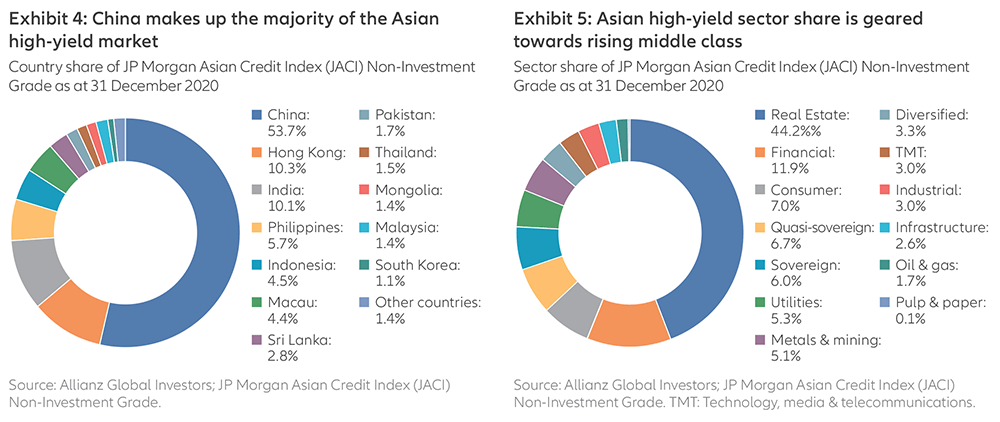

China, including Hong Kong and Macau, account for nearly 68.5% of the JACI Non-Investment Grade Index (see Exhibit 4). China’s economy reportedly grew by 2.3% in 2020. While this is only about a third of the annual growth rate China has reported in previous years, it was most likely the strongest among all other major economies – most of which contracted sharply last year. With its economy expected to grow by more than 8% in 2021, China should continue to anchor market sentiment and capital flows into Asia, particularly if tensions with the US de-escalate under the new Biden administration. For all its peculiarities, China looks more like a “normalised” market with higher real (after-inflation) yields than most advanced economies. China’s 10-year debt currently trades at more than 200 basis points of extra yield than 10-year US Treasuries, and more than 350 basis points higher than 10-year German bunds – which currently yield around -0.5%.

Despite its strong growth and productivity, some investors are wary of high leverage in China’s corporate sector, which accounts for about 60% of the country’s debt and more than 150% of GDP. These figures are higher compared to those for other emerging markets, the US and the euro area. Since 2010, low funding costs in US dollars have encouraged corporations to increase their offshore debt issuance.

Nevertheless, additional credit metrics suggest China’s debt is largely sustainable. An OECD analysis of the 2004-2019 period suggests that China has a comparatively lower share of non-investment-grade companies at risk of not meeting future interest payments using internal cash flows. Moreover, China ranks better than the US on a ratio of non-financial listed corporate debt to EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation). A strengthening economic recovery and local currency (the CNY rose nearly 7% against the USD in 2020) are enabling China to start levelling off its debt while other countries ramp up borrowing to tackle the pandemic.

India, the Philippines and Indonesia, together with China, make up about 88.5% of the JACI high-yield index. Countries in East and South Asia have been less successful in curbing the spread of Covid-19, but they are expected to rebound to positive economic growth this year as the global vaccination rollout begins to take hold. Leading manufacturing indicators for most Asian economies are now either above the expansionary threshold or have moved nearer to it.

The Philippines are likely to have suffered one of the worst economic contractions, but the balance sheets of its larger corporations look more resilient than in the past. Indonesia’s economy probably fared better, though its debt markets have been more prone to capital flight due to the relatively large share of foreign investor holdings and higher exposure to volatile commodity prices. In India, the recession was probably deeper and there are concerns about its larger fiscal deficit and lower credit ratings. Having said that, the recovery (as in China) has recently broadened out to the services sector. The IMF now expects India’s economy to grow by more than 11% during the next fiscal year (April 2021–March 2022).

Improving demand and debt dynamics

More than 75% of Asia’s offshore high-yield market is dominated by real estate, financial, consumer and sovereign-related issuers – all operating in sectors which are highly geared towards Asia’s rising middle class (see Exhibit 5). About half of the world’s middle class now lives in Asia, and in turn China accounts for half of that share. While China’s recovery in 2020 was powered largely by real estate and infrastructure investment, domestic consumption is trending upwards and now makes up roughly half the country’s GDP. China’s focus on further boosting domestic demand and import substitution, as well as on creating regional growth, bodes well for businesses that have a domestic or regional bias.

Rated high-yield issuance in Asia reached USD 37.7 billion in 2020, the second highest annual level on record, with 76% of total issuance coming from China property companies according to Moody’s. The real estate portion of the market is the most active in primary markets and the most liquid in secondary markets, offering a full yield curve unlike many other sectors. China’s real estate bonds are attractive for investors looking for high carry, typically trading at a more than 5% premium over their peers outside of Asia. Despite the sector having borrowed aggressively over the last few years to fund land purchases, default rates remain low.

Housing demand continues to be supported by strong urbanisation trends. Some of the larger developers are already reporting improved contracted sales and uninterrupted access to debt financing, particularly those with relatively light offshore refinancing needs over the rest of this year. Even weaker issuers in the single B-rated segment, which saw their yield premium over BBs increase substantially last year, have recently issued new bonds at lower borrowing costs than in the fourth quarter. Late last year, China introduced new guidelines for banks and developers to help limit leverage in the property sector, which has long relied too heavily on rolling over short-term and uncommitted credit lines. Asian USD high-yield leverage in 2020, measured as the ratio of net debt to EBITDA, probably grew by less than a factor of 1. Cash as a percentage of total debt also looks encouraging, at broadly similar levels to those enjoyed by the investment-grade segment of the JACI index.

Outside of real estate and construction, repayment and default risk in most other sectors across Asia is even more idiosyncratic. Tighter onshore credit conditions may exert high pressure on more commoditised and oversupplied sectors – such as industrials, metals and mining – as well as exposure to local governments with less fiscal room to manoeuvre. Overall, Asian defaults in 2020 were not much higher than in previous years. In fact, the number of first-time defaulted issuers in the China onshore market declined from 2019.

What caught the market somewhat by surprise last year were several high-profile defaults by state-owned companies, more so than in previous policy tightening periods. While there were certain specific reasons behind this string of credit events, they also signal China’s move to de-emphasise implicit government guarantees for poorly managed enterprises, and to promote better insolvency and resolution practices. Over time, a more market-based approach should benefit investors by introducing a clearer differentiation between healthier and weaker credits.

Active risk and return potential

In the long run, Asian high-yield returns are largely driven by coupons and interest accrual, which make a strong investment case for long-term allocations to the asset class. Ideally, investors should be nimble with single position sizing, and favour credits that they would be comfortable to hold to maturity. At the same time, this is a market that is challenging to track using passive financial instruments – either because these are not available, or because credit and illiquidity risks are so inextricably linked. Occasionally, many benchmark bond issues, and even issuers, are not readily traded in the secondary market.

With a size of less than USD 300 billion, Asia’s USD high-yield market is relatively small and concentrated. To expand the opportunity set and add to risk diversification, it’s important to be active in deploying dynamic and off-benchmark strategies. These include allocations to cash and investment-grade corporates, and sometimes to onshore (local currency) credit markets – which can offer a broader representation of corporate Asia. Growing foreign access to onshore debt – for example, via the Hong Kong China Bond Connect platform – could help more Asian corporations refinance at home, something that would be credit-positive for their offshore outstanding debt.

Investors’ intent in allocating to Asian credit is no longer just opportunistic. While an estimated 80% of the market is still held within Asia, foreign investors have been steadily increasing their participation, subscribing to about a quarter of new bond issuance last year. With more than 70% of developed-market government bonds in negative-yielding territory, and the average investment-grade corporate bond yield at a record low of less than 2%, we may be seeing the precipice of a more strategic asset allocation shift to Asia and China. This shift has already accelerated in equities, and high-yield credit is well-placed to follow suit.

Accelerating Digital Transformation

AI & Software-as-a-Service

Summary

Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) – also known as cloud-based software – is a method of software delivery that allows data and applications to be accessed from any device with an internet connection and web browser.

Key takeaways

|