“We caution against taking current consensus forecasts at face value. While a scenario of moderating growth or mild recession is undoubtedly possible, there are several reasons to think things could turn out differently.“

Stefan Hofrichter

Head of Global Economics & Strategy

Slower growth – better returns?

The consensus view on global economic growth – and, in particular, on US growth – remains rather benign. Most commentators expect a “soft landing” for the US economy – where the central bank successfully slows the economy without triggering a recession – or only a mild one. A deeper recession is considered only an outside risk.1

In fact, only around two in five US economists anticipate any recession in the coming quarters.2 International institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) see moderating growth globally followed by a rebound during 2024. Central banks’ growth forecasts concur. The relative resilience of economic activity so far – especially in the US – supports this benign outlook.

But we caution against taking current consensus forecasts at face value. While a scenario of moderating growth or mild recession is undoubtedly possible, there are several reasons to think things could turn out differently.

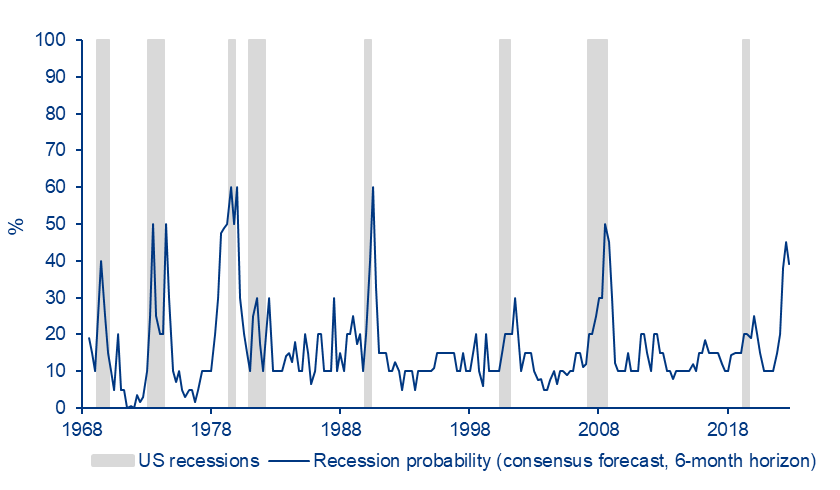

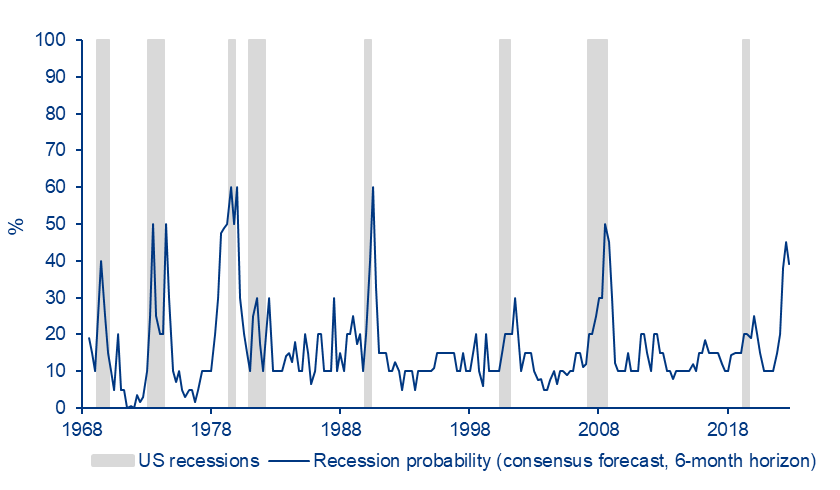

First, economists are notoriously bad at anticipating recessions (see Exhibit 1). Even on the eve of the most severe downturn in decades – the global financial crisis – most expected a soft landing.

Second, various leading indicators are still consistent with a US recession starting between the end of 2023 and the first half of 2024: this is the signal we get from the inverted yield curve, money supply contraction (because of central bank tightening) and the fact that central bank rates are above neutral levels and therefore in “restrictive” territory.

Inflation: stubbornly high

At the same time, inflation remains quite stubborn and significantly above the major central banks’ targets of 2%, despite being significantly down from the peak inflation rates of 2022.

We find the resilience of inflation unsurprising: the sharp rise between 2021 and 2022 was driven not only by the Covid and energy price shocks, but also by excessive liquidity in the system following massive monetary policy easing.

Three longer-term supply side shocks are also contributing to structurally higher inflation. The first is deglobalisation – or, more precisely, the fact that trade as a share of global domestic product (GDP) is trending down, because of a greater regionalisation of supply chains among other factors. Decarbonisation and a structurally tighter labour market due to demographic changes are other factors.

We know from previous experience that, after a period of high inflation, it can take several years for inflation to fall back to low levels due to second-round effects, such as wage-price spirals (where higher wages lead to higher prices and so on) or mark-up pricing by companies.

Against this backdrop, we question whether markets are correct in pricing in no more rate hikes by major central banks and significant rate cuts starting in mid-2024. In summary, we expect “higher for longer” rates than the scenario priced by consensus.

Perhaps this consensus reflects the expectation that higher productivity growth could help lower inflation? It is true we are seeing major technological changes, with generative artificial intelligence (AI) being only the latest example. These advances might lift aggregate supply in the world economy and thereby – potentially – help bring down inflation. The jury is still out, however. So far, productivity growth numbers are not showing signs of a structural increase. Also remember that, while productivity growth can be supported by technological innovation, it can also be held back by factors like “malinvestments” and the prolonged fallout following the burst of credit bubbles or wars, as history shows us.

A peak in bond yields?

Yields at their highest levels for more than one and a half decades, with an economic downturn looming, would typically make high-quality sovereign bonds objectively attractive. However, we think timing the peak in bond yields remains difficult. We would be more comfortable if the market pricing of central banks’ future rate path was more conservative and reflected “higher for longer” rates.

Investors should be attuned to the potential end of the Bank of Japan’s (BoJ) long-standing policy of capping long-term interest rates, a move that could have spillover effects for the global bond markets. Energy prices are another wild card, particularly following the horrific attack on Israel in early October 2023.

We think growth expectations need to be adjusted downwards, and therefore risk assets are likely to face more challenges and higher volatility. It has typically paid off most to add to equities and spread products during recession – not ahead of one. And any potential repricing of bonds would likely have repercussions for equities.

The past two years have also been characterised by “accidents” in the financial system: in 2022, the UK pension system came under stress, while in early 2023 we saw the failure of several banks, notably in the US. The worst may be behind us, but we cannot rule out more events, as the Financial Stability Board, the IMF, central banks and other institutions repeatedly remind us. High leverage in the world economy and sustained higher interest rates are a recipe for financial instability. This time, there may be more risk in non-bank financial institutions, rather than in the banks. Some tail-risk hedging might be a good idea.

Exhibit 1: Economists have consistently failed in anticipating recessions.

What about this time?

Note: Recession probability based on the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia's Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF). Chart matches the expansion/recession periods in the US with the median recession probability of the survey two quarters ago.

Source: Allianz Global Investors Global Economics & Strategy, Bloomberg (data as at 30 September 2023). Past performance is not an indicator of future results.

1 Source: Bank of America’s global fund manager survey, October 2023.

2 Source: Consensus Economics, October 2023.